Protecting Cabernet Sauvignon

There’s no doubt that Cabernet Sauvignon is among California’s most important wine grapes. Across the state there are nearly 95,000 acres of it planted and the grapes that result produce some of the most collectible, sought-after and highest-quality wines of the world.

It is also among the grapes that helped put Northern California on the map internationally after the Judgement of Paris Tasting in 1976. But its roots in Sonoma County go way farther than that.

The year 1875 was a turning point in Sonoma County wine history, the first time it led the state in wine production. As detailed in Sonoma Wine and the Story of Buena Vista by Charles L. Sullivan, Cabernet Sauvignon was already in the mix.

Around this time, the widow of William Hood, Eliza Shaw, began grafting Mission vines planted on her Los Guilicos land grant in Sonoma Valley to Cabernet Sauvignon, Riesling and Semillon.

John Drummond came along in 1878, buying a large piece of the Los Guilicos Ranch and planting 150 acres. The ruins located on the site of what is now the property owned by Kunde Family members under the original name of Wildwood Vineyards, Drummond’s Dunfillan Winery sourced from vines that had been imported by Drummond from Bordeaux, including Cabernet Sauvignon from Chateau Lafite. Before long, his grapes were commanding top dollar from area wineries, as sought after as those planted by H.W. Crabb in the 1860s over the mountain at To Kalon.

Fast-forward to the 1930s and Simi Winery in Healdsburg, under the leadership of Isabelle Simi Haigh (who owned Simi until 1970), was earning a reputation for fine Cabernet Sauvignon.

In the 1940s, Frank and Antonia Bartholomew paid $17,600 for the long-shuttered Buena Vista Winery, which was being auctioned off by the state. Professor Albert Winkler of UC Davis paid a visit and suggested they grow, among other varieties, Cabernet Sauvignon. Before long, the great wine consultant Andre Tchelistcheff was on board to consult after making his mark at Beaulieu Vineyard in Napa.

Still, for a long time, Cabernet Sauvignon was nearly a specialty crop. In 1964 there were only 89 acres of it in Sonoma County; by 1971 it was up to 1,629 acres.

The year 1972 is when the real post-Prohibition planting explosion began. By the end of that year Cabernet Sauvignon had grown to 2,469 acres in Sonoma County, 65% of which were still unbearing. Through much of the 1980s, 570 acres of grapes were added per year, and then between 1993 and 2012, Cab plantings grew another average of 1,300 acres a year.

Today, Sonoma County has the third largest amount of Cabernet Sauvignon in California – around 13,000 acres – exceeded only by Napa and San Luis Obispo counties. But its long legacy here is clear and it is a resource that should be protected.

Cabernet tends to thrive in the warmer reaches of plantable land. Here, a majority of the Cabernet is found in Alexander Valley, Knights Valley, Dry Creek Valley and at elevation on Moon Mountain and Sonoma Mountain, all traditionally warm areas.

What used to be considered warm is often now much warmer, and water resources are always of concern. So it was good to hear of a new UC Davis study published in Frontiers of Plant Science that looks at one way to grow Cab in warmer environments.

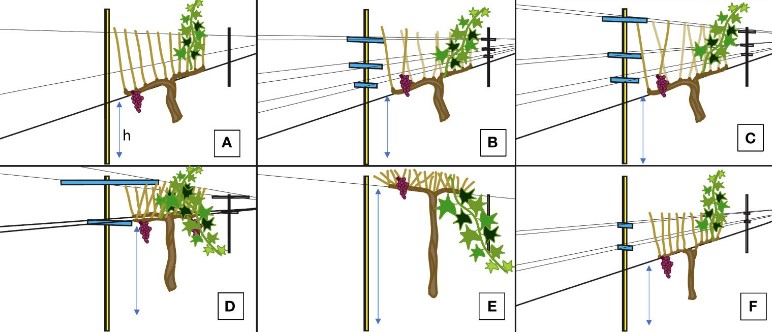

The study maintains that single high-wire trellis systems allow vine leaves to shade grapes better than vertical shoot position, or VSP, trellises, where vine shoots are trained to grow up in vertical, narrow rows with fruit growing lower to the ground, allowing greater exposure to sunlight. How much sunlight depends on the site and the farmer.

VSP trellises became popular during the boom planting years of the 1990s and allow more rows to fit per unit of land than many other systems. They were actually first used in cooler areas of Germany, France and New Zealand to ward off fungal diseases and maximize sun exposure.

In California, this is less of an issue in many places.

Examining six different types of trellis systems and three different watering amounts, the study also found that single high-wire trellis systems got a more marketable yield for the amount of water used. It also found that single high-wire trellis systems acted like a good shade cloth but didn’t negatively affect grape color or quality.

Whether or not this change in trellising makes sense for growers in Sonoma County remains to be seen. But it could be something to consider long-term. Given Cabernet Sauvignon’s long history in Sonoma County, it has a proven ability to survive.

FIGURE 1 Illustrations for the Trellis Systems Established at the Oakville Experimental Vineyard: (A) Traditional Vertical Shoot Position (VSP); (B)Vertical Shoot Position 60° (VSP60); (C) Vertical Shoot Position 80°(VSP80); (D) High-Quadrilateral (HQ); (E) Single High Wire (SH); (F)Guyot-pruned Vertical Shoot Position (GY). “h” stands for the cordon height from the vineyard ground.